AWARDEES: Stanley Cohen

SCIENCE: Cytokines

FEDERAL FUNDING AGENCIES: National Institutes of Health

Stanley Cohen

The eggs were slated for the trash.

It was the early 1970s, and Dr. Stanley Cohen, a Brooklyn-born experimental pathologist, was working hard to learn more about lymphocytes, then the newly discovered source of the antibodies that the body uses to fight off viruses and other outside invaders. The lymphocyte is one of several kinds of “white blood cells” that together provide protection against disease. Stan was on a mission to learn more about how lymphocytes could induce immune responses even in instances where no antibodies were present; this was the case for tuberculosis, a serious illness of the lungs.

He knew that, in addition to antibodies, lymphocytes incubated with a foreign invader, known as antigen, could produce substances called lymphokines that affected the behavior of other inflammatory cells. However, there was no evidence that these substances that were found in test-tube cultures were actually produced in the body. He wanted to prove that they were.

In order to understand how the production of lymphocytes led to immunity, Stan needed a way of selectively deleting other parts of the immune response, and he spotted a paper saying a virus infection could do just this. That’s where the chicken eggs came in. To get enough virus, he needed to grow it in fertilized eggs. “It would have been a better narrative it I had used goose eggs,” he says now with a grin.

As it turns out, Stan was not able to reproduce the finding that viral infection led to immune suppression. With progress elusive, he had to concede that his gamble had failed. “It just didn’t work,” he recalls. “Here we were, with a lot of infected eggs all set to be thrown out.”

Then Stan had a thought. Was it possible that those infected eggs could make the same kinds of immune response that the lymphocytes did? It turns out: They did. It was a very exciting and unexpected finding, he recalls, since the infected eggs had no immune system, and it led to the thought that perhaps every cell type could make these so-called lymphokines. What was special about lymphocytes was that stimulation with antigens triggered them. In the case of the fertilized eggs, it was the virus that was the trigger. Stan predicted that different cell types would require different triggers. This ended up to be the case; often, the trigger is merely the presence of other cells.

The experiment led to Stan’s hypothesis that most if not all cells could secrete factors that affected the behavior of other cells (not just lymphocytes), and that the phenomenon went beyond just the immune system. He named these factors “cytokines” – cyto to represent “cell,” and kine, because it reminded him of the action word “kinetic,” and because, well, it sounded nice after cyto. In science, Stan says, “nothing seems real until you name it.”

“What I used to tell my students,” he recalls, “is that the most interesting things sometimes come out of results that are negative. Why discard something without seeing what’s going on?” The chicken egg experiment proves the point. Afterward he immediately set about exploring the implications of his novel, unexpected finding. The first question? Whether it was a peculiarity of the eggs. So Stan next tested the concept in human kidney cells … and the same thing happened. He went on to explore the role and actions of various cytokines in test tubes, animals, and ultimately, human disease.

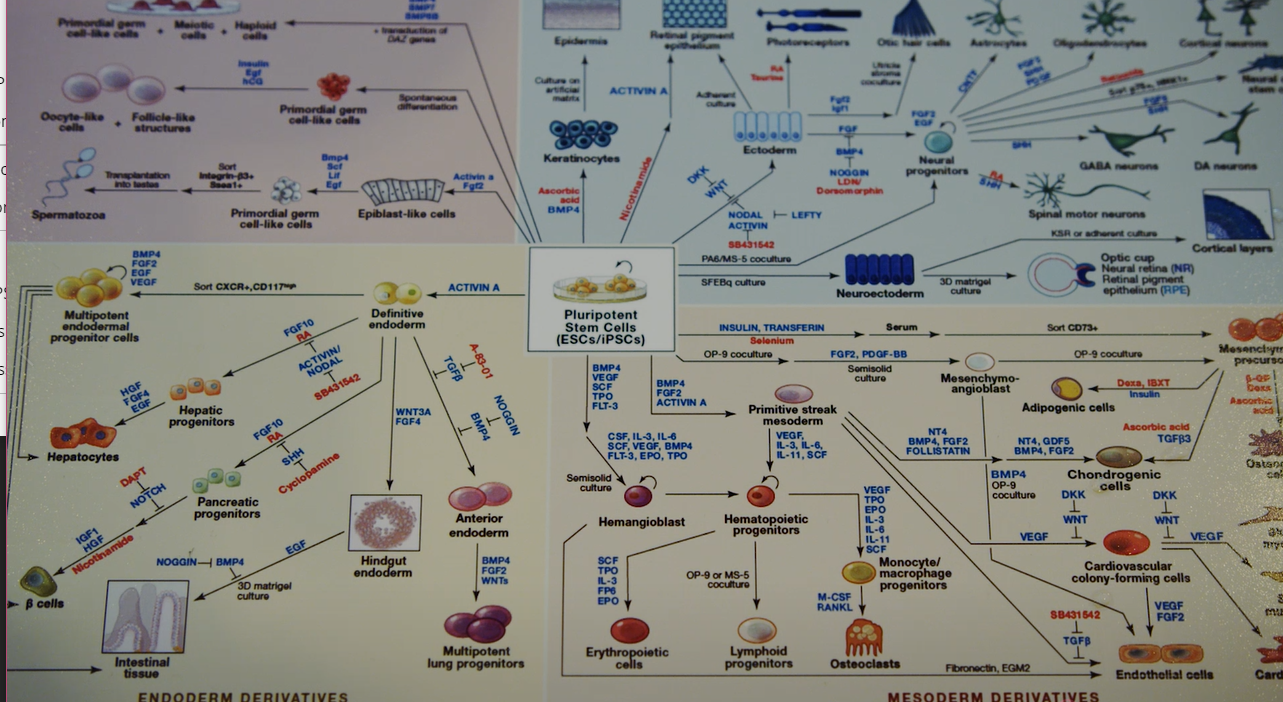

But it wasn’t easy. At first, Stan recalls, “no one would believe that a non-immune cell could secrete the same factors as an immune cell and repurpose them.” The cytokine concept was sufficiently strange that his first paper on the subject was initially rejected for publication. But as time and science moved forward, other researchers began to take note. Stan’s initial observations led to a series of experiments by him and many others that firmly established the concept of cytokines, and an explosion of cytokine research began. Essentially, cytokines are the vocabulary of the language that cells use to communicate with one another. The network of cytokines regulating cellular interactions is incredibly diverse; more than 100 cytokines have already been identified, and they play a role in growth, development, defense against disease, and cancer. Scientists have since shown that they play important roles not only in protection from disease, but also in the normal workings of the body, and they play these roles in every organ system studied to date, both in adults and in embryonic development.

For Stan, prestigious papers and boosts in research funding followed his breakthrough, including an “Outstanding Investigator Award” from the National Institutes of Health in 1986. But he is quick to acknowledge that it was NIH’s investment in his early work that enabled the cytokine findings, thanks to his grants related to cancer and cellular activation. It is another case, he says, of basic research taking an unexpected turn.

A 2004 interview with Stan in a journal called – yes – Cytokine, stated that five journals at the time had the word “cytokine” in their name and that hundreds of books in many languages referred to it. “It is interesting,” he said in the interview, “that a concept that I initially had trouble getting published took on such an astounding life of its own.”

The biggest surprise for Stan, though, has been the therapeutic potential of cytokines. Cytokine research has led to new therapeutic approaches to cancer as well as enhanced treatments for a variety of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Cytokine-based therapeutics account for a sizable percent of the world’s biopharmaceutical market; as of 2011, more than 120 companies were developing more than 270 therapies that involve cytokines, according to the Cambridge Healthtech Institute Pharma Reports.

After making significant contributions to the world of immunology and pathology, Stan went on to found and direct the Center for Biophysical Pathology at Rutgers. Throughout his career he was active in scientific society leadership, editorial boards, and federal peer review panels, and in 2015 he was awarded the American Society of Investigative Pathology’s lifetime achievement award, the Gold-Headed Cane.

After Rutgers, he tried retirement, but it didn’t last. “I decided I had no retirement skills,” Stan says. Since the cytokine system comprises such a vast network, he is now using machine learning and artificial intelligence to work to fully understand it and sort out the underlying mechanisms of complex diseases. His wife, Dr. Marion Cohen, is a tumor immunologist who has made important contributions regarding the interaction of cytokines with tumor cells and endothelium, cells that line blood vessels and other spaces in the body. Their collaborations have led not only to many scientific publications, but also to three children who have grown to become research-oriented physicians. You could say science is in the blood in the Cohen family – or perhaps, the cytokines.